I decided to revisit the original Mixed Fragility piece that I wrote back in May 2020. This is my 2.0 version after spending the last few years fully awake and embracing my Blackness. So, buckle up and read about my evolution and reintroduction to myself.

I felt like I’d been hit on the head — not hard enough to knock me out, but just enough to wake me up.

And once awake, I couldn’t go back to the way things were.

For years, I was uncomfortable being vocal about the racism I saw and experienced. I felt silence was safer. Politeness felt protective. Assimilation felt like survival. But I now understand that my silence didn’t protect me; it only delayed the inevitable reckoning. So, I’ve pushed through the discomfort because remaining quiet has cost me far more than speaking up ever has.

Antiracist educator Robin DiAngelo put words to something I had already been witnessing for years: white fragility. It shows up when white people are challenged about race and immediately become defensive, angry, afraid, guilty, or shut down altogether. Instead of leaning into discomfort, people often respond by arguing, deflecting, or staying silent. And those reactions aren’t accidental. They work to restore comfort, to reset things back to “normal,” and to avoid the hard, necessary conversations that real cross-racial understanding actually requires.

When I first learned the term, it felt like I had been given new glasses to see clearly with. The more I named racism out loud, publicly, without softening, the more I watched white fragility surface in real time among people I know deeply, and those who only know me at arm’s length.

But what I didn’t yet have language for was my own.

I came up with the term mixed fragility because of my tendency to be defensive, wounded, angry, or dismissive toward the Black community itself — stemming from years of internalized self-protection and self-hate. A fragile balancing act founded on the idea, learned early and reinforced often, that proximity to whiteness might shield me from harm. At the same time, complete identification with Blackness might cost me acceptance, opportunity, or safety.

Even writing that sentence makes my chest tighten.

This realization didn’t come easily. It came with grief, shame, and a deep sadness for the girl I once was — the one who learned very early that belonging always came with conditions.

I grew up in Macon, GA, in a family that was educated, where going to college was not just an option; it was a given. On my mother’s side, both grandparents were college graduates. My parents (divorced when I was 2 ½ years old) both earned master’s degrees; my mother went on to earn two Ph.D.s.

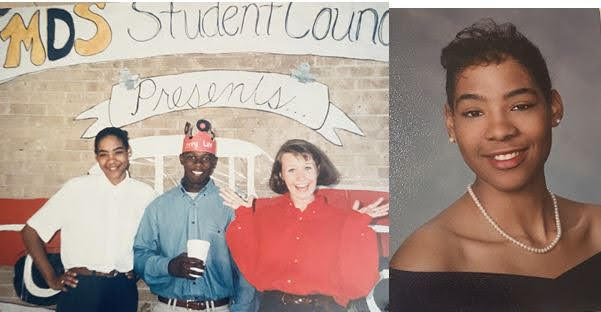

Raised Catholic, I attended St. Joseph’s Catholic School for elementary, Mount de Sales Academy for high school, and later The College of Saint Rose. For much of my childhood, I was either the only Black student in my classes or one of just a few until high school. My mother and I were also among the few Black parishioners at our church.

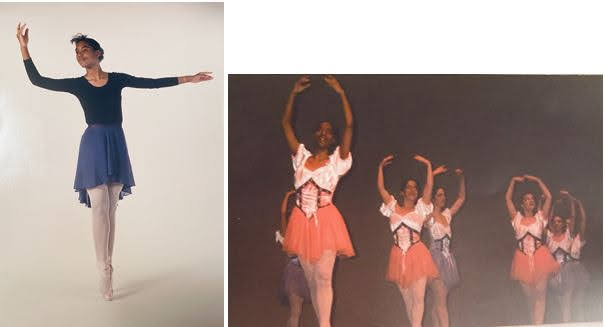

I took ballet. I threw myself into community theatre. I lived on stages and in rehearsal spaces where, again, I was usually the only Black person present. These spaces became my refuge. They developed me artistically, emotionally, and socially, but they also isolated me in a somewhat protected bubble that I wouldn’t fully understand until much later.

Outside of my family, I had very little sustained Black influence growing up. And when I did encounter Black peers — at summer camps, in school, later in college — I was often told I was “too white,” a “sellout,” that I “talked white.” I wasn’t trying to reject anything. I was just trying to be myself during years that were already painfully awkward.

Those words stuck. They hardened something in me.

My mixed fragility responded with resentment: Why am I being punished for liking what I like? For loving Anne of Green Gables? For being theatrical, articulate, earnest? I felt judged, so I judged back. I now know that both sides were operating within systems that taught us to police one another rather than interrogate the structures around us.

I often felt suffocated by insecurity and a sense of not belonging anywhere.

In high school and college, that suffocating grip deepened. I was the only Black cheerleader at Saint Rose in Albany, NY, during my sophomore year in the late 90’s. At basketball games, I heard Black students jeer from the stands: “Quit acting white.” “Cheerleading is for white girls.” I smiled through it until I couldn’t anymore.

I left the team the following year because there are only so many ways you can fracture yourself before something breaks.

What I didn’t yet have language for back then is a term I hear often now: Predominantly White Institution (PWI) trauma. Being in these spaces caused a severe psychological toll, hyper-visible and invisible at the same time. Constantly performing excellence while absorbing microaggressions and outright hostility, recognizing that your presence is conditional.

Despite all of that, I still found myself gravitating toward whiteness.

White friends often told me, “I don’t see your color.” I interpreted that as a compliment. In my mind, it meant they saw me as one of them. I didn’t yet understand that what they were really saying was that they didn’t see the parts of me that required them to change, to listen, to be uncomfortable.

And still, acceptance was never complete.

I wasn’t invited to certain birthday parties or sleepovers because parents didn’t allow Black children in their homes. A boy who had been my dance partner in multiple productions at Macon Little Theatre wasn’t allowed to take me to prom. His parents said, “It’s one thing to be on stage with a n****r, but quite another to be seen in public with one.”

As an adult, I’ve been followed in stores like HomeGoods and Target because I apparently look threatening when wearing a fascinator or vintage hat and carrying a purse that matches my shoes. One of my “favorites” is when someone asks me where something is in the store, assuming I work there. It took years for me to say: You’re being racist. Do I look like I’m wearing a uniform? They always seem shocked and backpedal. I usually just shake my head and walk away.

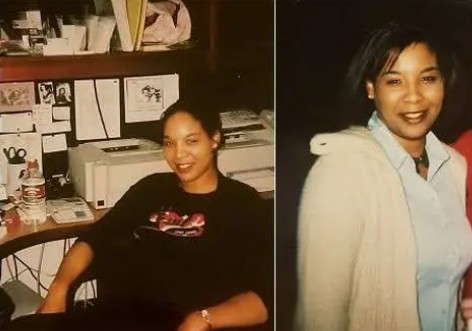

Then I entered the workforce.

And that’s when I learned “my place.”

No one prepared me for how little my talent would matter once I crossed that threshold. No matter how educated or accomplished I was, I would still be seen first — and often only — as a Black woman. My tone was policed. My ambition is labeled aggression. My confidence read as arrogance. My mistakes were magnified while others were given grace and second chances.

I wasn’t prepared for how exhausting it would be to prove I deserved to be there constantly.

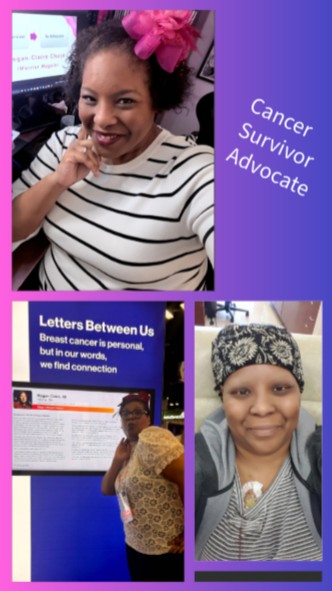

And then came breast cancer.

Cancer didn’t just attack my body; it crippled my momentum, nearly crushed me financially, and derailed professional goals. It interrupted opportunities, altered trajectories, and forced me to rebuild yet again in a system that already offered so little grace.

Surviving cancer is supposed to make you feel victorious. Grateful. Courageous.

Instead, I grieved the career that never got the chance to fully breathe because of surgeries and toxic treatments. I was told I had to choose between my work and my health.

I longed to support myself through media, storytelling, advocacy, and the stage, but anxiety and insecurity kept pulling me under. I wanted to amplify my voice without diluting myself to be palatable or safe.

When Donald Trump entered the White House for the first time, the hostility and overt racism intensified. The permission slip for racism felt signed in bold ink.

I remember a white woman in line ahead of me at the pharmacy pointing at me and telling her misbehaving child that I would “ram my cart into him” if he didn’t behave. It wasn’t an anomaly. It was witnessing, in real time, how hatred is taught. That little boy is being taught to associate Black people with violence.

When I shared that story publicly, many white friends asked why I didn’t say something. They couldn’t understand my silence. But my silence saved me. I think about all the viral videos of white women weaponizing fear, and how deadly the consequences can be for Black people who speak up.

The most painful part?

Another white woman witnessed the entire interaction.

And said nothing.

I am still working through my mixed fragility because the trauma runs deep. But I am no longer confused about this:

I am not protected. Black people are not protected.

My education doesn’t protect me.

My eloquence doesn’t protect me.

My proximity to whiteness never did.

Discovering the works of James Baldwin in 2020 changed everything. My mindset recalibrated in ways that shocked me. As attempts are made to erase Black History, I am grateful for Black creators who ensure our stories endure — reminding me that others’ inferiority projections are not mine to carry.

I have reclaimed my voice.

I speak up for myself and others, even when labeled an “angry and arrogant Black woman.” I don’t care anymore because silence is no longer an option.

Racism exists and is wrong.

Racism infects healthcare and cancerland.

Willful ignorance is wrong.

And while I continue this internal work, I need white people, especially those who say they love and support me, to do their part externally.

Speak up.

Intervene.

Risk discomfort.

Vote with Black people, not against us.

You may not be able to change a racist. But you can change an outcome.

Until next time,

Warrior Megsie

Thankful to know you, my friend. You open my eyes a little more every time we interact and I’m forever grateful for your advocacy. I will never truly understand as a white woman and it helps me see a little more how I can use my own white privilege for my mixed race family.

LikeLike

Thank you for trusting us with this. I read it slowly and more than once.

As a white woman, a breast cancer survivor, and an oncology nurse, this piece challenged me in ways I needed to be challenged. Not because I don’t care or haven’t witnessed racism in healthcare—but because you articulate so clearly how silence, comfort, and proximity to whiteness allow harm to continue even when intentions feel “good.”

Your reflections on mixed fragility, PWI trauma, and conditional belonging landed deeply. They made me examine the ways healthcare spaces—spaces I work in and care deeply about—can still reproduce the very harms we claim to be healing. Especially in cancer care.

I’m grateful for your honesty, your refusal to soften, and your insistence that love and support require action, not just words. I hear your call to speak up, intervene, and risk discomfort—and I take that seriously.

Thank you for reclaiming your voice and sharing it so generously.

LikeLike